Explosions in a Paint Factory:

Art You Can Hear

South End News, July 24, 1997 [vol. 18, No.26]

by Christopher Millis, Living Arts Editor

Just when you thought you’d seen the last of abstract expressionism, color for color’s sake, shape for the sake of shape, along comes Roger Goldenberg to invigorate a style you were ready to file away under recent history.

Goldenberg’s show is as unexpected in its anachronistic vitality as it is in location, happening as it does at a gallery which has prided itself on the work of representational painters and sculptors. Unlikely stylist meets unlikely space with the result that “Memory Pieces,” the title of Goldenberg’s exhibit, is one of the most compelling displays this summer on Newbury Street , where compelling shows are as infrequent as memorable Hollywood movies.

What does it take to create excitement where the forerunners seem to have used up all the excitement? It’s a question that bears close relation to how one competes as a second-born child when one’s elder sibling has earned the first flush of parental thrill and undertaken a new generation’s initial encounter with the world. What’s left for the latecomer? As it turns out, plenty, but it’s a plenitude almost necessarily hard fought.

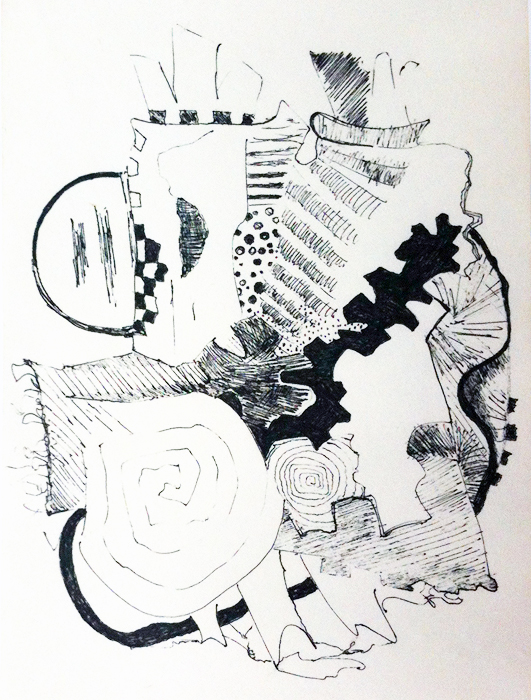

In the case of Goldenberg, one is first struck by the boldness of his colors, the shameless eruption and commingling of primary and secondary shades. That in itself wants to sound like near-empty praise for a relatively small accomplishment. It is neither. When you consider the big names of Abstract Expressionism—Paul Klee, Jackson Pollock, Paul Jenkins—boldness of color has little place in their oeuvres. The movement’s progenitors were relatively bashful when it came to the brightness of their acrylics and oils; they were also relatively austere when it came to the variety of colors they employed. Goldenberg’s frames are marked neither by shyness nor by austerity; they are like explosions in a paint factory. Anything can happen, and often it does.

Goldenberg’s use of color, however, is inseparable from his elaborate, complex, playfully inventive designs, beginning with his recasting of the tractional, quadrilateral, single-plane frames. In fact, there are exactly two works in the entire exhibit that measure in as squares. The rest are multiple pieces of wood intersecting or built up on top of each other, often at a 45- or 90-degree angle to the adjacent piece. For all the squareness of each constituent part, taken together, the whole of each construction appears to be an aspiring wheel. The result is that the tumult of color within the painting finds both a counterpoint and a complement in the unpredictable contours of the circumference. Among the remarkable achievements in this show is one’s sense that the crazy, angular dimensions of his paintings’ overall shapes—their outlines often suggest the shapes of kimonos for the genetically challenged—seem positively natural, inevitable extensions of the inner workings of each piece.

More to the point, Goldenberg’s compositional acuity, his arrangement of dense patterns beside more open patterns, his juxtapositions of lines and curves, his overarching harmonies composed of jarring, discordant elements, bear an affinity, as the artist acknowledges, to the musical movement of jazz. Not that one needs to be a jazz aficionado whatsoever to appreciate the integrity of Goldenberg’s designs. However, the proximity of order to chaos, of passion to cerebration, of the foreknown to the reckless, makes the sound of jazz, the best jazz, inspired jazz, a close metaphor for Goldenberg’s achievement.

These are paintings that one could listen to forever.

Note: {this article is accompanied by a photo of Jazz Improv, 1997 with the caption, “Can You Hear It?”}